REVIEW: The Prince of Egypt (1998)

“No kingdom should be built on the backs of slaves.”

The Prince of Egypt was DreamWorks SKG’s second film release and their first traditionally animated movie. In 1998, a faith-based, $60 million epic was quite a gamble for the fledgling animation studio. Simon Wells, Steve Hickner, and former Disney story artist Brenda Chapman would direct the film, with Val Kilmer leading an all-star cast. The Prince of Egypt brings to life the story of Moses and the Hebrews’ plight in Egyptian bondage.

This is a film I had as a kid, and I’ve known it as long as I can remember. However, I really didn’t care for it much until more recently. I found some parts frustrating, like Yocheved putting Moses in the basket and Rameses attacking the Hebrews after releasing them. I also found much of the dialogue and character work dull as a child, and now that’s my favorite stuff. Really, I think these are the types of things that can make any film great. I think it was courageous for any Hollywood studio, but particularly a brand new animation house, to make a film like this. As an agnostic myself, I think anything associated with religion, especially the Abrahamic religions, tends to draw ire from many people. I’m not in the “Christians are a persecuted minority” camp, but most religious films that come out are ridiculed. In fairness, however, most of them are worse than this. Even the most basic marketing materials for a movie like God’s Not Dead or Breakthrough elicit as many groans and laughs as cheers. However, I’ve only ever heard of a nonreligious person having an ethical issue with The Prince of Egypt once. This is actually the film that made me want to go back and review DreamWorks movies and is quite possibly my favorite of theirs. This is the type of movie I wish Disney was brave enough to make. It’s also one of the few religious movies I admire as a film, an adaptation, and an exploration of spiritual questions and themes. The closest any other film has come to this rare experience for me is Disney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and even that is different on several counts. For one, while it explores the good and bad in religion and deals with ethical and spiritual questions, Hunchback isn’t an inherently religious movie. Although it may seem random to compare the two, I feel similarly about The Prince of Egypt as I do about Hamilton. Both represent things that, at least on paper, I am not interested in and shouldn’t like. They both take characters from familiar stories that we take for granted and create complex heroes and sympathetic villains. Let’s dive in and see how great God’s wonders can be.

Every aspect of this production is top-notch, from the stunning animation to the cutting dialogue to one of the most impressive casts I can think of in any modern film. The Prince of Egypt came right off of Antz’s heels, and honestly, no two of DreamWorks’ movies are more different. Both strive to be mature and adult; there’s clearly a concerted effort to rise above the stupid assumptions surrounding the animated medium in America. However, Antz seeks to differentiate itself from Disney and Saturday morning fare with sex jokes and PG-13 language. The Prince of Egypt grapples with challenging themes and morally compromised characters on both sides. Rather than asking you to believe in God or even believe these events indeed took place, the film merely requires you to suspend your disbelief during its brisk runtime. The Prince of Egypt doesn’t busy itself with convincing the audience of anything. Instead, it does what any great story should: it introduces memorable characters and, through their interactions and conflicts, raises some hard questions and crafts a story so engaging you can’t look away. This is one of those rare movies I really could talk about all day. So, for the sake of simplicity, I’m going to break this up into categories.

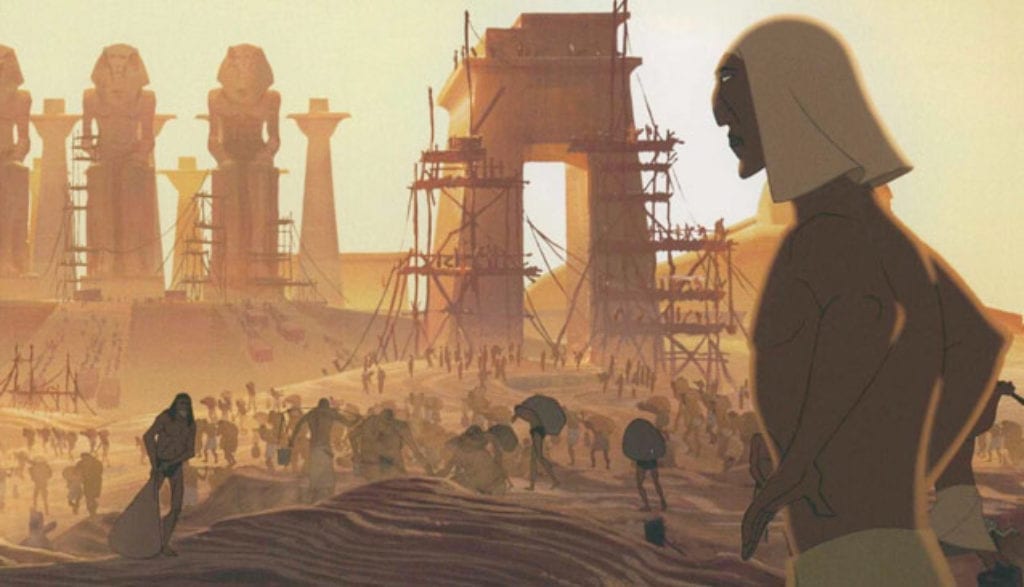

For me, visuals are the least important aspect of film. Film and television are inherently visual media, so I realize how strange this may sound. However, I mean to say that all other criteria I consider to have greater weight in the film’s overall quality. There are films I don’t find visually appealing, but which have such great characters and/or story I don’t mind. But if I’m not invested in the characters or what happens to them, no amount of aesthetic beauty can compel me otherwise. A good example for the former would be Quantum of Solace, the latter Pocahontas or The Last Jedi. Thankfully, The Prince of Egypt is a movie that doesn’t ask you to choose; every frame of this 100-minute movie is so striking and gorgeous it could be a painting on your wall. This film’s visual style is so ambitious that I almost can’t believe this studio produced the hideous Antz only two months earlier. The animators create a world that feels both vast and unjust within the first 30 seconds. We see Hebrew slaves toiling in the heat, the only source of shade being towering monuments to the Egyptian royal family. The oppression of slavery is communicated beautifully, instantly, and without a word of dialogue. Animated films have to be more economical because everything has to be created from the ground up, and The Prince of Egypt doesn’t waste a single frame.

There’s something to be said about the use of color in this film, too. As in The Ten Commandments decades earlier, Moses is associated with the color red, and Rameses blue. This could be read as a visual representation of Moses’ tendency to outward emotional reactions and Rameses’ to stuff everything down. From the beginning, Moses’ words are given significant weight even with his adoptive parents. At the same time, father Seti constantly berates Rameses and shuts him down. Rameses feels just as strongly about everything as Moses does. In some cases, his emotions are felt more deeply by the audience, thanks to the incredible character animation done by Dan Boulos and Darlie Brewster. The effects work in this film is also breathtaking. All of the big moments are conveyed unbelievably well; the burning bush, the parting of the Red Sea, and the plagues are some of the big visual scenes that come to mind. But that’s just the obvious stuff; the character animation, landscapes, weather, textures, and just about everything you see in the film are just gorgeous. A reviewer I used to like listed an issue with the film being the exaggerated character designs, given the epic scope and somber tone they went with. However, I don’t think a movie has to be just one thing to be good. A movie can be both silly and heartbreaking, and for me personally, those are some of the best cinematic experiences. Animation is also the art of exaggeration; if I wanted to see real people, I’d just watch The Ten Commandments. These designs, which you could call “cartoonish” are also partially responsible for under-appreciated aspects like the telling facial expressions on a character like Rameses. Even when he says nothing, you always know exactly how he feels, and often find yourself empathizing with him.

This film also sounds incredible in all areas. This is a rare animated film where every vocal performance is pitch-perfect, eliciting all the right emotions and easing you into this world through its people. I mentioned earlier the astounding cast this film has, and it really is kind of mind-blowing. Val Kilmer starts out arrogant and childish as Moses, later growing to be humble and empathetic. He doubles as God, a cute little trick a few Bible adaptations have done to show how we’re all made in God’s image. It’s hard to say, but I think Ralph Fiennes gives the best performance in the film and has the most challenging role. Michelle Pfieffer is feisty and smart as Tzipporah, and I actually like how her relationship with Moses unfolds. Sandra Bullock is excellent as Miriam, and I frequently forget she’s played by a celebrity. The acting in this movie is so good that you often forget there is acting happening. Jeff Goldblum, Danny Glover, Patrick Stewart, and Helen Mirren play smaller parts, but they’re all just as good as you’d expect. As Seti, Sir Patrick paints an image of a distant father and a cruel, unempathetic man. Helen Mirren’s Queen Tuya is a more loving parent, although perhaps one who can’t understand what her adopted son is going through. Steve Martin and Martin Short are also pretty funny as a couple of Egyptian priests Moses and Rameses torment as boys.

Action is put to sounds that fit and aren’t distracting, and in sound editing, that’s the highest praise. In many modern action/adventure movies, the dialogue is drowned out while action and any commotion make you want to turn the stereo down. And of course, it’s impossible to talk about this movie and omit the soundtrack. This is truly a powerhouse musical, with score by Hans Zimmer, songs by Zimmer and Stephen Schwartz, and collaborations with the likes of John Powell and Harry Gregson-Williams. The songs in The Prince of Egypt push the characters and story forward, and they’re absolutely gorgeous and captivating musically. “Deliver Us” bookends the film beautifully, and Ofra Haza is simply haunting as Moses’ biological mother, Yocheved. “All I Ever Wanted” is an interesting way to turn the traditional Broadway “I Want” song on its head as Moses goes into denial upon realizing he’s a Hebrew and the relevant implications. I don’t want to go too much into the songs as they’re really something you should experience for yourself. They’re all accompanied by fantastic animation to create some truly memorable scenes. However, I will just say that “The Plagues” is my favorite song and one of the best sequences in the film, truly delving into just how far apart Moses and Rameses have drifted. It’s also an epic, honest look at how the Plagues affect the innocent citizens of Egypt as well as Pharaoh and the Hebrews.

This leads me to the final category I want to talk about today and its greatest strength, its characters. I tend to think of Bible characters, especially those of the Old Testament, as being pretty black-and-white morally speaking, and rather one-note. The Prince of Egypt works wonders in exploring any complexity one could imagine for its two central characters, each a masterpiece in character development. Rameses and Moses experience somewhat opposite arcs, and the result is something really brilliant. In the beginning, when Moses’ basket arrives at the palace, the Queen sets Rameses aside to cradle the strange baby. This may be reading in a little bit, but I always took this as a gesture meant to communicate that she shows a preference for her younger, adopted son. After all, she shows more tenderness towards Moses than Rameses in their teenage years. This is even more true with Seti. He shows affection for Moses a couple of times in his brief screen time and is always blaming Rameses for any and all trouble the boys get into. He tells him that “one weak link can break the chain of a mighty dynasty!,” creating something of a complex in the crown prince. When Moses returns to Egypt to free the Hebrews, we immediately become aware of a change in Rameses. From this point on, most of his decisions are made to strengthen his rule and the family’s overall position in history. He yearns to be just like Seti but even better, even bigger, as is evidenced by his statue situated right next to his father’s, and over which it towers. As I alluded to earlier, this film effectively communicates a lot of information with a single image or line of dialogue. As a teenager, Rameses was somewhat fun-loving and willing to get in trouble, albeit not as much as Moses, as Rameses was the one who always had to face the consequences. When Moses reunites with his brother, he finds an older, hardened man who isn’t willing to lose face or make any mistakes. Rameses is burdened and defined by his crown, the responsibility of rule, and a deep fear instilled in him by a distant, controlling father. While Moses is the more sympathetic and righteous character by the film’s end, Rameses is my favorite in The Prince of Egypt. Part of this comes down to the incredible vocal performance provided by Ralph Fiennes. He also sings during “The Plagues,” and is excellent there too. This man should look for more singing opportunities in his roles.

However, this character also has some of the most striking, telling facial expressions in the film. Rameses is very calculating in what he does and says. In many cases defers to his advisors, again showing a large contrast to his younger self. He gets a lot of excellent dialogue, and his relationship with Moses as his older brother is very believable. This character is a tragic villain, another case of this film delivering something we don’t see so much in western animated films. This was more true in 1998 than it is now, what with Disney’s ridiculous list of recent plot-twist villains. It’s always a little heartbreaking for me to watch Rameses’ face and body language when Moses leaves Egypt, and even more so when Moses returns years later. Rameses is legitimately so happy to see his brother, who he thought was gone forever. He doesn’t care that Moses became a farmer, that he’s a Hebrew, or about anything, for that matter. Both when the brothers are kids and when they’re reunited as very different men, Moses is the only person Rameses will betray his usual behavior for. Just as he would goof off and take risks with him years ago, as Pharaoh, he’s willing to set aside Moses’ heritage and prolonged absence, publicly declaring him “our brother Moses, the Prince of Egypt” and pardoning any and all crimes associated with him. Even though this man keeps the Hebrews as slaves and seeks to expand on his father’s ideas, it kills me when he realizes Moses isn’t here to stay or reminisce on old times. Rameses doesn’t understand why things can’t be the way they were, why Moses suddenly cares so much about “(his) people” and their freedom. It’s amazing how no matter what this character does, they use the magic of animation and voice acting to show you his perspective. The plagues could be stopped at any time if he would release the slaves, but that’s not how Pharoah sees it. From his perspective, this is all a cruel trick his brother is playing on him, and he just doesn’t know why. Rameses’ character development is in direct contrast to Moses’, as he strays more and more from doing what’s right. He doesn’t consider actually releasing the Hebrews until their God has murdered his only child, the thing he loves most in the world. This is another devastating scene, and it’s just dripping with atmosphere. Seeing Rameses slowly but carefully carry his shrouded son to rest tells you everything you need to know. But they don’t stop there; the screen is bathed in white, defined by the shadows of the father and his motionless child. Moses tries to comfort his brother, but Rameses shrugs away from his outreached hand, merely giving him permission to lead the Hebrews away and harshly whispering to “leave (him).” His choice to ultimately chase Moses and his people with the Egyptian army, which I couldn’t make sense of when I was younger, makes more sense to me now. Rameses simply can’t let go of the way things were. First, he has to let go of his brother, then eventually, his parents. Moses comes back and gives Pharoah hope, but he’s just here for his people, not his brother, who he abandoned. He’s then forced to say goodbye to his only son and heir, and, resigned to this losing streak, he frees Egypt’s slaves. While it’s undeniably wrong on numerous levels, his final attack does make sense for the character. After having time to regain some composure, it’s easy to imagine Rameses didn’t want to accept the personal defeat or, more importantly, the apparent weakness of freeing his enemies to reward their insolence. After the battle, the final image of Rameses is one of him alone in a cavern, crying out to Moses. His men are all dead, his slaves and brother are gone, he has no family or friends anymore. He still has his kingdom, but he is utterly defeated and broken. Yet even now, he still can’t let go of Moses or the past they shared when things were different and simpler. Rameses has grown to hate his brother for all that has transpired, but deep down, I wonder if part of the disgraced Pharoah still longs for things to again be as they once were.

Moses’ part of the story is equally compelling to watch if a little less unique to the medium. His arc runs parallel to Rameses’, but is in many ways, its direct opposite. I like how this is visually displayed during “The Plagues.” Moses is an aspirational figure, a boy who grows up selfish, entitled, and cruel, but becomes a noble, generous man. Miriam spurs a crisis in Moses by alleging that he is her brother, and therefore a Hebrew slave by birth. At first, comforted by his mother, the Queen, Moses tries to go about his normal life, trying to convince himself that the royal life is “all (he) ever wanted.” But he grows intolerant to his people’s treatment, lashing out and unintentionally killing an Egyptian servant for cruelly whipping a slave. Upon realizing the extent of what he’s done, Moses runs away. Rameses temporarily stops him, promising to use his power to “undo” the accident and protect his brother. Moses can’t do this, though, and tells Rameses to “go ask the man I once called father.” This refers to another incredible scene in which Moses asked Seti to “Tell me you didn’t do this” to Hebrew baby boys. His adoptive father hugs him but coldly replies that “they were only slaves.” Truly great acting and visuals at this moment as well. Moses sadly but necessarily leaves his adoptive family behind, traveling into the desert and getting lost. He soon finds himself with Jethro and the Midian people, including his future wife, Tzipporah. They accept Moses as he is, and he becomes a humble farmer among them until one of his sheep strays, leading him to the burning bush, and the rest is history. I love how The Prince of Egypt portrays Moses as conflicted, firstly about leading the Hebrews in opposition to his former home and family. Then, even as the plagues escalate, he’s sympathetic and even sorry for Egypt’s innocent children and families. Although it was unwanted and rejected, his compassion and regret at Rameses’ son’s death were genuine. You can tell he hates feeling responsible for these things, and these are people he cares about getting hurt. It always bothered me how God is doing some really evil things that don’t really fit well into current beliefs in this story. I love that this movie confronts that directly and shows that even Moses doesn’t really agree with a lot of it. Still, he has to persevere for his God and his people’s freedom. The Prince of Egypt never takes the easy way out, and it doesn’t settle for the convenient, happy ending. When Rameses shouts out to Moses in the end, Moses quietly whispers “goodbye, brother,” and this perhaps hurts most of all. One final reminder that these men loved each other, lived as brothers, and that maybe in another life, it didn’t have to be this way.

The Prince of Egypt(1998)

Plot - 10

Acting - 10

Music/Sound - 10

Direction/Editing - 10

Character Development - 10

10

Outstanding

I'm not sure that any perfect movie exists in technical terms. However, The Prince of Egypt is a movie that perfectly hits every criteria that I think makes a movie great. Incredible visuals and music are paired with complex and pained characters to tell a thoughtful, engaging story.

Incredible review. You’ve read my mind on many things about the movie. How it’s similar in style and music to Hunchback, I mean the openings for them were great. It’s got one of the best casts in my book. It’s a bit ironic that Rameses that he was called a weak link and somehow Egypt was broken by him after the chaos. One of my favorite scenes would be when Moses tries to talk to Rameses and they ease for a few seconds remembering a memory before Moses left. Best animated film of 1998 in my book too.